Picture-Book Propaganda: E. Boyd Smith's Pocahontas at Plymouth

Sarah Ballan

[1] Author and illustrator E Boyd Smith (1860-1943) wrote a number of children's books published at the turn of the 20th century. His books are described as "rich time capsules into which we are free to peer," as they subtly twist the tales to align themselves with prominent views of his time, specifically the overbearing negative views towards Native Americans (Brooklyn Public Library). Smith strategically published The Story of Pocahontas and Captain John Smith in 1906, which coincides with the 300th anniversary of the Jamestown settlement. Two striking images in this book that exemplify the preferred British way of life while condemning traditional Native American culture are on pages forty-three and forty-seven. The first of these images shows a crowd of English people welcoming Pocahontas to Plymouth. She is escorted by husband John Rolfe and by Indian tribal leader Uttamatomakkin. The next image shows the same three figures interacting with the elite members of Britain's society. The language and illustrations in this children's book effectively produce an elevated image of an assimilated Pocahontas. Smith equates assimilation with positive and necessary change, simultaneously condemning traditional Native American culture.

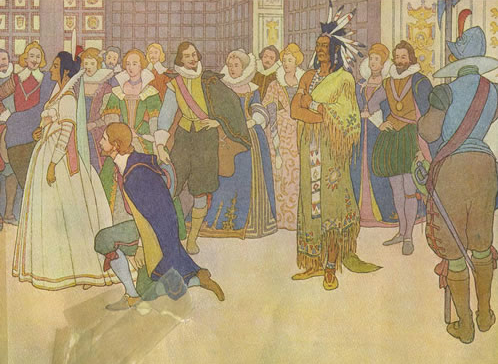

[2] Smith links assimilation to maturity and links failure to assimilate with simple-mindedness and defeat. In image one, Pocahontas is dressed in a proper British long dress; her hair is done up and neatly tucked into her fancy hat. Rolfe stands alongside the Princess, extending his arm in front of her as if announcing her presence. The Governor of Plymouth takes off his hat for Pocahontas, a polite gesture indicating he is pleased to make her acquaintance. In the narrative, Smith parallels assimilation and sophistication, writing "and here [in England] she grew to be a woman, and learned the ways of the English women, and dressed as they did" (40). In contrast, before coming to England Pocahontas is but a "little maid," though, of course, brave enough to stand up to her father and save Smith (25). Her womanhood is made possible by her English cultivation. As a result, her presence is widely accepted, and she is treated favorably. The rest of the crowds' gaze is directed towards Uttamatomakkin. His "war feathers and Indian Robes" appear tattered and unbecoming. He carries sticks in attempts to inefficiently count the number of English to report back to Powhatan. This disorganized method hints at the Native Americans' simplemindedness, and with a "disgusted grunt" Uttamatomakkin gives up counting the sticks (42).

[3] Even though Pocahontas and Uttamatomakkin are both Native Americans, they are treated entirely differently. Smith's images suggest that assimilation brings about positive attention for Native Americans, while failure to assimilate will ostracize them from the modern English society. In image one, the English people are wary of Uttamatomakkin because of his rugged appearance; they find the way he presents himself in traditional dress to be off-putting. In addition to the negative attention emphasized textually by his native dress of "war feathers and Indian Robes" (42), Smith creates an exaggerated physical space between Pocahontas and Uttamatomakkin, suggesting that he is an outsider. The fact that Rolfe stands between them indicates Pocahontas's acceptance into this new culture. Those looking in Uttamatomakkin's direction lean back with their mouths wide open and hands on their hips. Furthermore, dogs pull forcefully on his robes made from the "skins of the wild beasts of his forests," making it clear Uttamatomakkin is a stranger, or perhaps a threat to society, since dogs are domesticated animals who will attack strangers (45).

[4] Smith compares Pocahontas's stay in England to a "triumphal march," suggesting that her assimilation is a conquest (44). The English people took what was once a young girl with savage-like tendencies and made her pure. Although she is a "dark Princess from another world," she simultaneously has grown up to be an English woman (44). Pocahontas gains the respect of the most prominent figures in society, including high bishops, great lords and ladies, and even King James and the Queen of England, who dressed in their "rich costumes of state" to greet her (44). These people of great importance consider Pocahontas to be the founding mother of America, for without her Jamestown would have ceased to exist. Since she "had done so much to help the struggling English colonists across the sea," they all wanted to meet her and throw festivals in her honor (45).

[5] While people are in awe of Pocahontas and are "curious" to meet and greet the dark Princess, the same individuals show a general disinterest and disapproval of Uttamatomakkin (44). Smith writes that "in his wild dress, with his tawny skin and shining black hair, he was a strange sight to those who had never before seen a red American" (45). Although Pocahontas too is a red American, she has completely adapted to the English way of life and is therefore accepted and treated kindly. In illustration two, Pocahontas stands in front of Uttamatomakkin walking forward; her Indian past is now behind her. Uttamatomakkin stands distinctly apart from the crowd, his arms crossed in front of him in disdain.

[6] E. Boyd Smith's books establish what he deemed to be the civilized, correct, white way of society and simultaneously create an outcast (the Natives). Even though the Native people occupied the land first, they are considered the pariahs in his narratives. Seven years later, he published another picture book with condescending views toward Native Americans. The Railroad Book tells the story of two young white children on the train across the country. In their journey "over the prairies, their train stops at a picturesque water tank station where they peer through the window and see a small family of Native Americans. Smith chooses to draw these individuals from the back left, without a full face, making them unidentifiable. The children are intrigued when they pass Native Americans and imagine them selling pottery or beads, but they learn instead that they "were a most dangerous menace to everyone who tried to come out there, often attacking the settlers, or pioneers traveling with their prairie schooners, their big, tent-covered wagons" (39). However, Smith fails to mention the large-scale relocation of the Native tribes during the Trail of Tears and like removals that occurred in the half-century before. By narrowing his focus and infusing these negative turn-of-the-century attitudes toward Native Americans into children's books, Smith is essentially guilty of perpetuating these stereotypes for the next generation.

Works Cited

"About E. Boyd Smith." About E. Boyd Smith. Brooklyn Public Library, n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Smith, E. Boyd. The Railroad Book: Bob and Betty's Summer on the Railroad. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1913. Print. http://www.bklynpubliclibrary.org/hunt/38railS.html

Smith, E. Boyd. The Story of Pocahontas and Captain John Smith,. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and, 1906. Print. http://www.bklynpubliclibrary.org/hunt/pocahontas_book_images.html